August in Park Point is green and full of raspberries and jewel weed. A completely different world from the snow-dune blanketed peninsula of my last visit in April. This time I followed the map from my most recent drawing of Park Point to the location called Peabody’s Landing to confirm what I suspected from the research completed at my kitchen table earlier. The narrow sidewalk that runs from the trail to the shore of the Superior Harbor is a remnant of Peabody’s Landing, named for the ferry service run by Charlotte and John Harry Peabody, who lived on the Point.

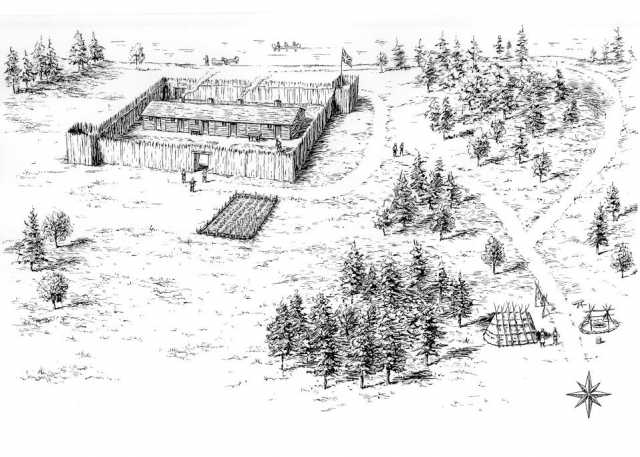

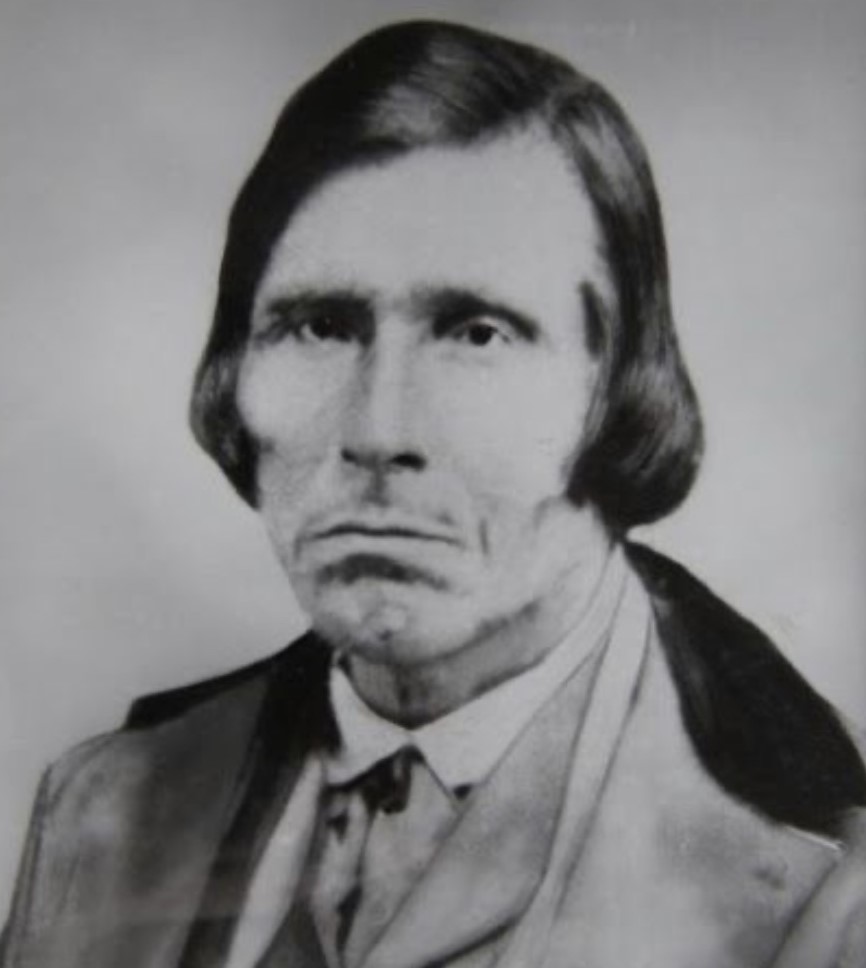

In 1853, George Stuntz, deputy U.S. surveyor, established a trading post, warehouse, dock and transfer company at the Landing. He ferried people and goods between Wisconsin and the Point and was granted exclusive rights of usage by the Territorial Legislature for a period of fifteen years. Stuntz traded with the Anishinaabe people for whom the Point was still a seasonal home and sacred site of their burial grounds. The 1854 Treaty of La Point established the Fond du Lac reservation and while the treaty was to maintain the Anishinaabe’s rights to hunt and fish freely outside the reservation, treaties were broken.

As early as the 1850s, vacationers made the short trip across the harbor to Park Point. By 1900s, the Peabody’s were ferrying the wealthy citizens of Duluth and Superior across the harbor to summer cabins built on federally-owned land. Superior’s Mayor Charles O’Hehir kept a cabin there from 1900-1927, and that Pine Knot Cabin was the last cabin on the site, razed in 2010.

References: