The Victorian home at 1122 Raymond Avenue with its asymmetrical shoulder slopes didn’t catch my attention at first, since the Victorians decorated with towers and turrets across the street feature more prominently in information about the area. The story of one of its first residents, however, illustrates a Black community rallying to support civil rights laws.

This house was built in 1885. The Saint Paul City Directories of the time list William Augustus Hazel and his wife Rosa at this address from 1896 to 1899. They had been living on the east coast where William had apprenticed as a stained glass artist and as an architect. The couple moved to Saint Paul around 1890 so William could represent the Tiffany Glass Company in Minneapolis (See 1890 article in the Appeal). The couple lived on the east side and Rondo before settling at 1122 Raymond for the last half of the decade, before William went on to academia, notably establishing the school of architecture at Howard University.

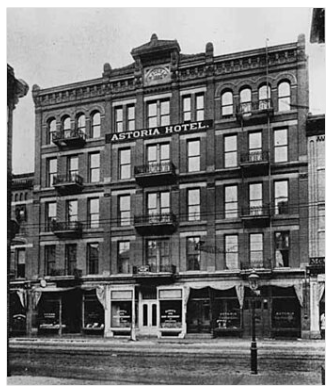

William’s introduction to Saint Paul was not full of welcome. An 1887 article in the Appeal describes how he was refused accommodations at the Clarendon Hotel (corner of Wabasha and 6th) and Astoria Hotel (374 Wabasha) due to the color of his skin.

William sued the hotels for $2,000 and won the high profiled lawsuit for $25 and community recognition for taking a stand.

While his impact on civil rights in Minnesota and work in academia live on, I was unable to find any of his creative work. Local work included the now demolished St. Peter’s AME Church (downtown St. Paul, Minnesota) created in 1888 and the 1895 stained glass windows in the demolished Austin Catholic Church, Austin, Minnesota.

The Montgomery Advertiser, Sun, Oct 17, 1993 ·Page 91

See William Augustus Hazel at 1122 Raymond in the Saint Anthony Park map.